By Michael K. Fisher

From Here to Equality: William Darity, A. Kirstin Mullen, and ADOS Deception by Misdirection

Reparations for American Slavery It Isn’t…

William “Sandy” Darity, Jr. is a professor of Public Policy, Economics, African and African American Studies at Duke University. Together with his wife, Andrea Kirstin Mullen, a folklorist, Prof. Darity recently published a 500 page tome titled “From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century”.

The book provides the academic underpinning for an on-line advocacy that purports to rename the African-American community as “ADOS” — an acronym for American Descendants of Slavery.

“Reparations are a program of acknowledgment, redress and closure for a grievous injustice. Where African-Americans are concerned, the grievous injustices that make the case for reparations include slavery, legal segregation (Jim Crow), and ongoing discrimination and stigmatization”, say Darity and Mullen.

They continue: “Closure involves mutual reconciliation between African Americans and the beneficiaries of slavery, legal segregation and ongoing discrimination against blacks.” Further, “Once the reparations program is executed and racial inequality eliminated, African Americans would make no further claims for race-specific policies on their behalf from the American government — on the assumption that no new race-specific injustices are inflicted on them”.

Lastly, while acknowledging that the enslavement of Africans in North America persisted at least from 1619 until 1865, Darity and Mullen advocate slavery reparations for African-Americans solely for the eighty-nine year period from 1776 to 1865.

Curiously, throughout the book the authors fail to specifically define the economic wealth-creating engine of slavery. Instead, by implication, they default to unpaid forced labor. It is this unpaid forced labor the authors seek to redress, demanding what amounts to back pay with interest in sufficient quantity to close the wealth gap that exists between the African-American community and the European-American community. Upon payment of this retroactive compensation, African-Americans will, so their promise, close their case for redress — all will be good.

Darity and Mullen are mistaken. Unpaid forced labor was not the engine that drove the enslavers’ wealth-creation. Unpaid forced labor was merely a feature of chattel slavery wealth creation. The engine was the systematic rape of enslaved black females.

How’s that? Well, not unlike today’s real estate industry, wealth-creation under chattel slavery was about expanding ownership of potentially income-producing assets that, rising in value, could be mortgaged to acquire more income-producing assets. That’s wealth creation.

The income produced by these assets had to be sufficient only to pay the recurring interest on the mortgages, some of the principal and miscellaneous expenses while the value of the assets rose in time. These assets, under chattel slavery, were the very bodies of enslaved black folk.

Houses can be built from brick, mortar, cement, wood and steel. Human beings can not.

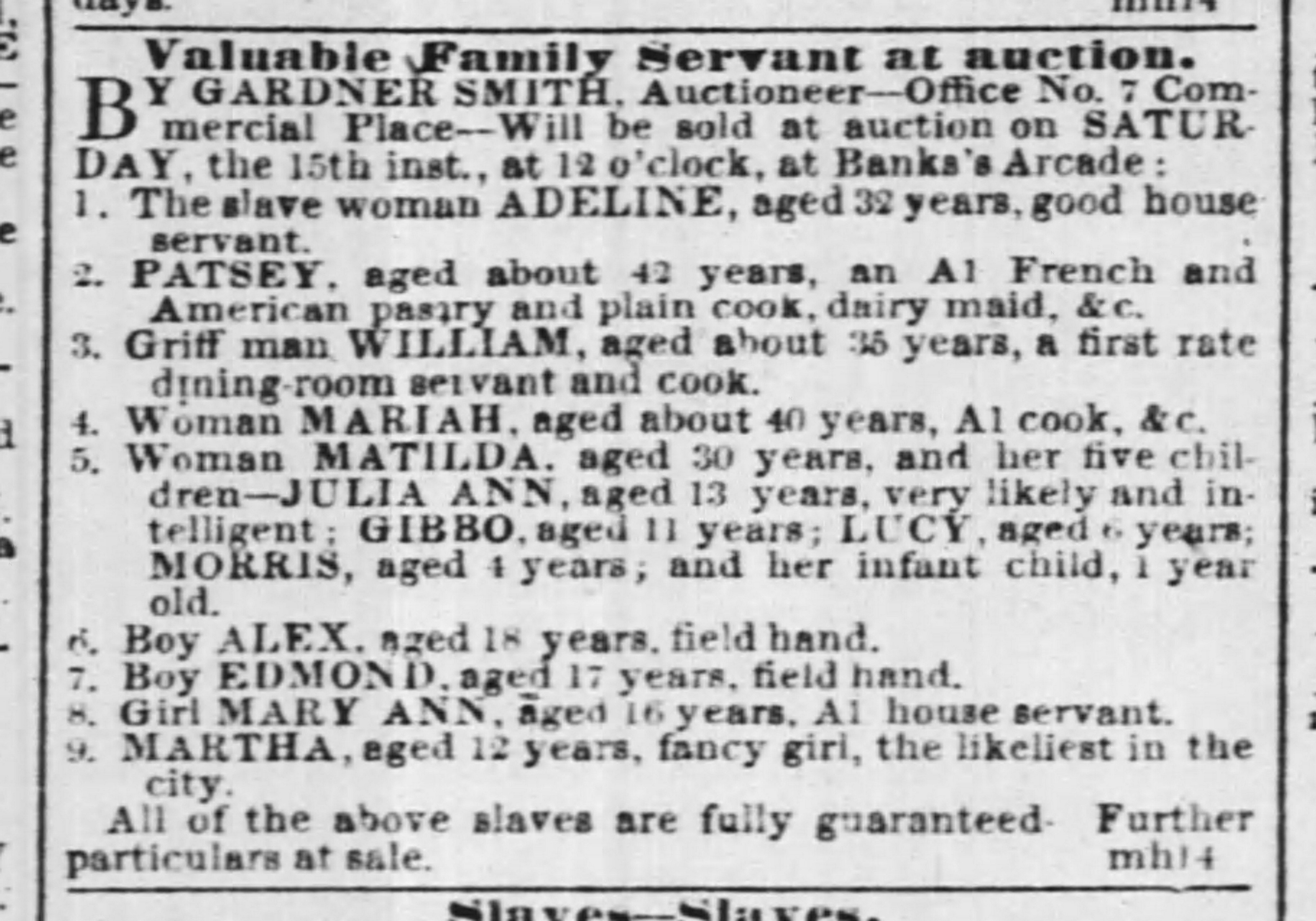

The imperatives of biology required the breeding of black females for black babies. That breeding, a controlled and manipulative process, by definition, took all the reproductive choice from the enslaved woman. It could only be obtained by rape. That rapist not only more likely than not being the white male enslaver, his son or an overseer, but also male “stud” slaves assigned by the enslaver to the task. The rapes universally began when the victims reached their menstrual cycles at about age 12.

No less a luminary than Thomas Jefferson — as “owner” of more than 600 human beings during his life-time certainly an expert on the subject of chattel slavery — explained the centrality of “breeding” that is, rape, to the creation of his wealth.

In a letter to Joel Yancey dated January 17, 1819 Jefferson explained “I consider the labor of a breeding woman as no object, and that a child raised every 2. years is of more profit than the crop of the best laboring man. [I]t is not their labor, but their increase which is the first consideration with us.”

Elaborated Jefferson in a letter to John Wayles Eppes dated June 30, 1820: “I know no error more consuming to an estate than that of stocking farms with men almost exclusively. I consider a woman who brings a child every two years as more profitable than the best man of the farm. What she produces is an addition to the capital, while his labors disappear in mere consumption”.

Imagine the daily terror of every enslaved black woman knowing that she was subject to inevitable multiple rapes at every minute of every day from childhood to late womanhood without recourse. Rape that was not just a matter of choice, but an economic necessity for the creation of the enslaver’s wealth.

There existed another systematic raping of black women that could only be conducted by white men. It is here where today’s fascination with light-skinned black women originates — namely the creation, through selective breeding, of “fancy girls”.

These were black females bred to resemble white females as closely as possible and sold, usually as children as young as 9, for the sole purpose of satisfying the sexual gratification (“fancy”) of white men, including white pedophiles. Their value was often three to five times that of the average field hand. The closer they resembled a white female, the higher their value. It is a valuation of black females by color that has been carried on to and infected today’s society.

How do Darity and Mullen address the rape of black women and girls as the indispensable engine of chattel slavery’s wealth creation? They don’t.

To the extent to which they address the rape of black women and girls at all, they trivialize this horrendous crime. In fact, they intimate that the enslaving rapists were merely “promiscuous” and at most engaged in “forced or mutually consensual liaisons with enslaved women”.

Mutually consensual? A slave? Even if such a thing were possible (it is not) what is a “forced liaison”?

Darity and Mullen’s “reparation” quite literally is the equivalent of demanding payment owed from a John that skipped out on such payment for his use of a child, that is, the rape of a child, forced into prostitution.

The pair does that, unless they are thoroughly incompetent as historians and economists, deliberately: by side-stepping the actual engine that, by the economic necessity of the chattel slavery system, drove the wealth-creation process.

Again: That engine was the deliberate, systematic, daily and hourly rape of black women. Without the million-fold rape of black women, the whole slavery wealth-creation system would have broken down.

Most every African-American family had to endure the systematic rape of their mothers, sisters and daughters. That certainly includes my family.

While I am happy to accept overdue payment for forced labor, that acceptance must not and can not result in the “closure” of the issues that have to be dealt with — central to which is the million-fold daily systematic centuries-long rape of millions of black women. Those women deserve recompense.

The claims resulting from these rapes have been passed down to the succeeding generations of African-American girls and women.

The claims need to be honored.

_______________

Literature:

Darity, William and Mullen, A. Kirstin, From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the 21st Century, 2020

DuBois, William Edward Burghardt, Black Reconstruction, 1935

Smithers, Gregory, Slave Breeding, 2012

Sublette, Ned and Constance, The American Slave Coast, 2016

_______________

Michael K. Fisher is the great-great grandchild of African-American women who were enslaved and raped in South Carolina.