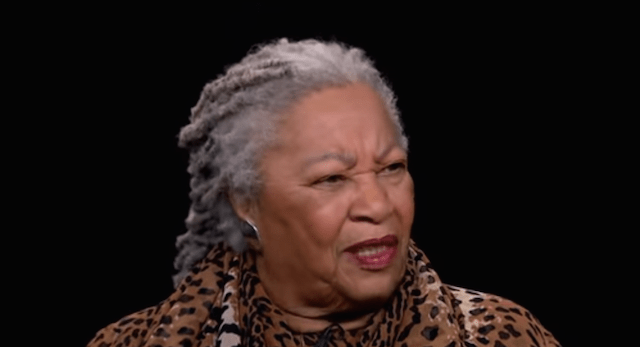

In an interview with journalist Charlie Rose, Toni Morrison discussed police brutality and violence against African Americans. She asked a series of questions that point to a key issue in America, the criminalization of Black skin and the white supremacist values cloaked in cowardice that leads to the deaths of so many unarmed Black victims.

She asked:

How are you afraid of a man running away from you?

How are you afraid of someone standing in the grocery store, on the phone with a toy gun, that you could buy in the store?

How could you be afraid of a little boy?

And who are these people calling who call 911? Who are they?

You look out the window and you see a kid with a toy gun and you get on the phone?

Her usage of the term “cowardly” speaks volumes in describing how institutionalized the dehumanization of Black people continues to be. The so called “fear” is based on creating a worldview of African descended people as less human in terms of intellectual prowess and super-human in terms of physical strength (especially when referring to criminality). This animalistic perspective has been at the center of anti-Blackness for centuries. Examples include when “scientists” debated the brain size of Blacks and religious leaders debated whether or not Africans had souls in order to deem slavery justified. It was the central theme of The Birth of A Nation, the 1915 propaganda film that overtly warned white Americans that free negros were a threat to society.

This would explain why someone could believe they have a logical explanation for shooting a person running away from them or gunning down a child and refusing to provide the child with medical attention.

They truly believe this unarmed person is “dangerous.” Officer Darren Wilson even described Mike Brown as a “demon” with the strength of WWF wrestler “Hulk Hogan.” That’s the thought process.

Super-human

Violent

Animalistic

It never changes.

Though Jonathan Capehart imprudently asserts the mantra “hands up don’t shoot” was built on a lie, the premise behind Mike Brown’s death follows the same superhuman negro/must be put down like an animal aggression trajectory. Whether or not his hands were raised, does not alter the key issue behind why Brown’s death was deemed justified. Simply put, he was perceived to be another dangerous negro.

Through this lens:

Mike Brown wasn’t a 17-year teenager. He was a raging gorilla loose on the streets.

Rekia Boyd was not an innocent bystander. Her very presence was violence as a potential threat.

Tamir Rice wasn’t a little boy. He was a roaming gunman looking for a victim.

Aiyana Stanley Jones wasn’t a sleeping little girl. She was a member of a familial mob the required brute force at first encounter.

With each death of an unarmed Black person, especially at the hands of police or people in assumed positions of societal authority, the cowardice and the fear is a reassertion of white supremacist beliefs, even if the victim dies at the hands of a Black police officer. Many members of mainstream media happily overlook this. Just as women can be patriarchal misogynists, Blacks can internalize Black inferiority and white supremacist beliefs.

Police have been given the authority to uphold laws and societal norms. While at the same time, the collective fear of Blackness operates as a U.S. societal norm. Thus the deaths of unarmed Black victims ensues, regardless of the ethnicity of the officer. When this occurs, the officers are then protected by the society that continuously protects and rebirths this norm.

Within the communities of the victims, they are seen as they are…human beings deserving of protection.

Mike was a teenager walking.

Rekia was a teenager standing.

Tamir is a 9-year old playing.

Aiyana was a 7-year old sleeping.

Amongst their communities, these victims are seen through a different lens..the lens of humanity. So when Toni Morrison asks, “How could you be afraid of a little boy?”

This question is very layered and could be interpreted as, “When will you see the little boy that I see?”

When will the lens be corrected?

Jessica Ann Mitchell is the founder of OurLegaci.com & BlackBloggersConnect.com.

Jessica Ann Mitchell is the founder of OurLegaci.com & BlackBloggersConnect.com.

To reach JAM, email her at OurLegaci@gmail.com.

Follow Jessica @TweetingJAM.

Follow OurLegaci at Facebook.com/OurLegaci.

Watch Toni Morrison’s interview below: